|

Is The Covid-19 Pandemic A Black Swan Or A Gray Rhino Event?

Part 4: Why do gray rhino events reoccur? Important policy shifts required

Sagar Dhara

Gray rhino events happen all the time and everywhere. A few of the recent gray rhino events are—the 9/11 World Trade Centre bombings in New York in 2001, the 2020 Australian Bush fires, the 2008 global financial crash, the 2018 extreme rainfall event in Kerala, the 2009 swine flu. There were warning signs before each of these events; some were loud, and some were faint. We failed to hear or heed them. And each time a gray rhino lowered its head to charge, we beguiled ourselves into believing that it was only a threat and a charge will not happen. And after each charge we paid a heavy price in the form of high death tolls, and loss of business and property.

Gap between risk and human perception of it

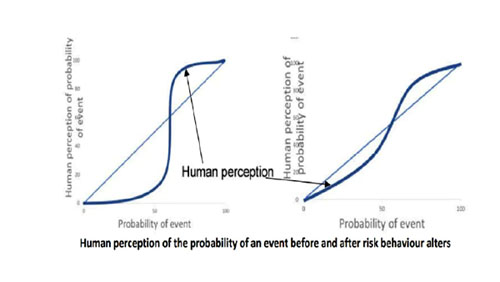

Human perception of risk is how humans—as individuals, organizations, and governments—subjectively assess the probability of a risk-bearing event happening. It is usually at variance with actual risk, i.e., the probability of a risk-bearing event happening. Human response to risk is driven by the human perception of risk, and not risk itself.

When risk from an event is low, human perception usually fixes it at an even lower level, consequently humans under-respond to the risk such an event poses, e.g., most smokers believe that their level of tobacco consumption will not harm them, and continue smoking. When risk is high, human perception tends to over-estimate risk and over-respond to the event, particularly if they feel that the risk is so high that death is imminent. For example, when the Bhopal gas leak happened, many persons abandoned their families and fled. Fear for their personal lives was so high that their family members no longer mattered.

Risk perceptions and responses are sometimes baffling and go contrary to trends. The Ersama super cyclone had a risk of 5,000 in a million (5000E-6) chance of death, considered as a high-risk. Yet, Odisha government’s sluggish action was due to its perception that the Ersama cyclone is likely to be of low intensity like the Ganjam cyclone that hit Odisha 10 days before the former.

In August 1994, Surat was struck by the ‘plague.’ It was a low-risk event with a mortality rate (5E-6) that was a thousand times smaller than that of the Ersama cyclone. Yet, fear of the plague caused an exodus of half million people from Surat. And that fear was not confined to Surat. A Delhi-based scientist who worked with the National Centre of Communicable Diseases, visited Surat to study the plague. When he returned home from Surat, he found that his home had no water or electricity. His neighbours had cut them to drive him out of their colony for fear that he carried back the plague. A family that fled Surat and sought shelter with friends in Thane district in Maharashtra was murdered by a neighbour for the same reason.

Risk perception is influenced by public memory which often is based on the experience of a few events. Public memory is short. In the last hundred years India has seen several epidemics, but they have slipped from public and government memory. India lost almost 40% of 50 million persons who died in the 1918 Spanish flu, the largest number of deaths from any country that was hit by this pandemic. The Spanish flu contributed to an anti-British sentiment in India as this disease was brought to India by Indian soldiers who fought in World War 1 in Europe as part of the British army. But the British showed little care for India’s plight. Yet, there is little mention of the Spanish flu in Indian history.

Risk response is driven by economic status, culture, and a society’s belief in its ability to control the course of events. The confidence with which Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and South Korea fought the coronavirus is due to their experience and success in battling the SARS and other epidemics, and the knowledge that they have a robust public health-care system.

Altering risk behaviour

To mitigate risk, it is not material whether risk or human perception of it is greater. What matters is the gap between the two. The larger the gap between them, the more difficult it is to alter human behaviour to risk and consequently mitigate risk.

Though India was aware of the Wuhan outbreak for a month before the first Indian case was reported end-January, the Indian government woke up to coronavirus risk only in mid-March. They had under-assessed the coronavirus risk and are under-prepared for it, just as they had under-assessed risk of numerous gray rhino events that have occurred in the recent past—1984 Bhopal gas tragedy, 1999 Ersama cyclone, 2001 Bhuj earthquake, 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, 2005 extreme rainfall event in Mumbai, the 2009 Kedarnath cloudburst 2015 extreme rainfall event in Chennai, 2018 extreme rainfall event in Kerala, 2018-19 heat waves in India. The loss of life in these events ranges 500-50,000. The Machlipatnam cyclone is a rare success story of an impending disaster being successfully averted. India’s preparedness in disaster management is rather poor.

Attempts to reduce risk through rules, laws, legislation, curfews, fines, campaigns, and other administrative methods do little to alter human behaviour to risk unless accompanied by programmes geared to alter risk perception. For example, campaigns to wear car seat belts and helmets by 2-wheeler riders have been unsuccessful in India.

For an effective risk response, perceived risk should ideally converge actual risk. Such a convergence can be achieved best through the active involvement of risk bearers in risk mitigation programmes. There is then a strong case for community participation in risk mitigation. The strength of such a programme is the community’s readiness to tackle risks they perceive as important. In the weeks after the Surat plague ended, communities in Surat cleaned up their neighbourhoods without help from the municipal corporation.

Risks are tackled at four levels—local, national, regional, and global. Dehydration can be tackled at the local level with oral hydration therapy. Extreme weather events such as the 2018 heavy rainfall event in Kerala, can be tackled at the state or the national level by preparing emergency response plans and conducting mock drills in communities. The Asian Brown Cloud requires cooperation in the South Asian region. And the ozone hole in the atmosphere needs global cooperation.

Unlike most other hazard issues, COVID-19 must be tackled at all four levels. Interestingly, the coronavirus war is making South Asia to foster regional cooperation again.

Prioritizing profits for business over reducing risk for people

In the early-1990s, Surat was a boom town riding the globalization wave. It became the world’s biggest diamond cutting and polishing centre because of its skilled and cheap labour. Diamond cutting business owners became millionaires overnight. But Surat neglected basic city sanitation. Filth floated in heaps all over town and Surat earned the dubious distinction of being named the filthiest town in Western India. The Surat plague caused Gujarat state huge financial losses.

The Surat plague was a consequence of prioritizing profits for businesses first over reducing risk for all people. The COVID-19 pandemic is also a result of this global outlook.

Transmission dynamics

To win the coronavirus war, it is important to understand its transmission pathways. Early information from a study being done by virologists in Heinsberg, the epicentre of the coronavirus outbreak in Germany, tell us that major COVID-19 outbreaks resulted from close gatherings over longer periods. Spread happened in Gangelt, a village in Heinsberg, after an infected couple were at a carnival there in February; in Italy after crowds gathered to watch football matches in Bergamo; and in Austria at the Ischgl ski resort.

There is little evidence to say that transmissions occurred through contaminated surfaces. The Heinsberg researchers swabbed doorknobs, mobile phones, toilets, remote controls, and other surfaces and found evidence of the virus on the swabs, but could not replicate the virus in a laboratory, i.e., the remnants of the coronavirus on these objects were no longer infectious.

Virologist Hendrick Streeck, the principle investigator of the Heinsberg study, said in an interview, “On the basis of our findings we’ll be able to make recommendations, It could be that the measures currently in place are fine, and we say: ‘Don’t reduce them.’ But I don’t expect that, I expect the opposite, that we will be able to come up with a range of proposals as to how the curfews can be reduced.”

The Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) emphasises that infection through contact with ‘contaminated objects’ has not yet been proven. Initial findings also indicate that that the chances of transmission in supermarkets, restaurants and hairdressers appears to be low.

A trickle of information from Wuhan points a finger in the same direction. The WHO report on the Wuhan outbreak states, “In China, human-to-human transmission of the COVID-19 virus is largely occurring in families.”

Virus transmission dynamics are contextual. While Heinsberg and Wuhan transmission dynamics may have takeaways for India, the dynamics in India needs to be understood. Being a big and diverse country, transmission dynamics may vary across the country. Consequently, disease control need not be a “one size fits all” strategy, which is what has been the thinking so far.

It is necessary for the government to explain its understanding of the transmission dynamics of coronavirus and justify its disease control strategy in that light.

Did lockdowns help?

For the last 3-4 weeks about a third of the world’s population is under some form of lockdown—local or national. Have lockdowns helped ‘flatten the curve?’ Are they more effective than other measures?

Most countries locked down when case numbers rose to high levels. India locked down when case numbers were low. A comparison of select countries that locked down and others that had not locked down but had controlled the disease (see Box 8) indicates that:

-

Locked down countries had a case per day growth rate mostly in double digits (7.8-17.5%). The high case growth rate in Germany is due to their extensive testing and detection of cases.

-

Despite a 4-week lockdown, India’s case growth rate for the lockdown period is 13.6% per day.

-

India’s high case growth rate during lockdown indicates that community transmission had started some time ago.

-

Transmission within the family may be a more important route for COVID-19 spread in India than was understood earlier.

-

Consequently, physical distancing, wherever possible, is an important mitigation measure.

-

Countries that did not lockdown but controlled the case growth rate started doing NPI early and implemented them strictly.

-

Countries in this sample that did not lockdown had a case growth rate largely in single digit (3.7-14.7%). The higher case growth rate of South Korea is attributed to extensive testing.

-

The NPIs generally followed by the non-locked down countries are extensive testing and surveillance, physical distancing, sanitizing, case isolation, contact tracing, quarantining suspect cases, use of personal protective equipment by health care and other personnel.

Based on the limited data from the sample of locked down and non-locked down countries presented in Box 8, the hypothesis[1] that can be drawn is that:

-

Countries that acted early and adhered strictly to NPIs were able to control case growth rates without necessarily having to resort to disruptive lockdowns.

-

Countries that locked down generally started doing NPIs late.

-

Lockdowns, particularly after case growth gains momentum, have not been particularly successful in controlling case growth rates.

If India’s current case growth rate persists till May-end, there will be about 50,000 cases by April-end, 4 lakhs by mid-May, and 3 million by end-May. These numbers may move upward or downward depending on the disease control strategy changes India makes after 3 May, and how successfully they are.

Good practice case studies

Two Indian examples stand out for the outstanding work they did to control COVID-19 spread—Kerala at the state level and Bhilwara at the district level.

The growth of cases during the lockdown period, 25 March-24 April for India and Kerala were 13.6 and 4.8% [2], respectively. How did Kerala reduce COVID-19 spread? When Wuhan happened, the Kerala government knew that the coronavirus would come to Kerala through students from the state studying in Wuhan. Their experience with the Nipah virus taught them to start preparing early, so they began planning in January.

When COVID-19 cases were first detected end-January, Kerala responded by testing aggressively for early case detection. At 610 tests per million population, Kerala’s test rates stand at one and a half the Indian average today. Kerala did painstaking contact tracing, longer quarantine periods, building thousands of shelters for stranded migrant workers, and distributing millions of cooked meals. To gain public support the Kerala government actively communicated with people, without which they could never have succeeded in doing early case detection and intense surveillance. They even planned evacuation routes for newly detected cases such that the patients had minimum contact with people along the way. The government made people their eyes and ears, and the partnership between the government and public helped to fight the coronavirus. Kerala is a model for the rest of the country.

Bhilwara, a textile town located in southeast Rajasthan, reported its first COVID-19 case on 19 March. This soon ballooned into 27 cases. Bhilwara district borders were immediately sealed, and four private hospitals and 27 hotels were commandeered by the district administration to accommodate cases. Between 22 March and 2 April, 22.4 lakh people were surveyed by nearly 2,000 health teams and 14,000 persons with flu-like symptoms were put on a watch list. The surveillance was relentless with visits to some houses made twice daily. Aggressive testing and contact tracing were done to identify cases. About 1,000 persons were put into quarantine centres and another 7,500 were home quarantined. On April 2, a complete lockdown was declared, and no one could step out of home. Cooked food was supplied to the poor, and fodder was distributed for cattle. The outbreak was quickly controlled.

The lessons from Southeast Asian countries that were successful in controlling virus spread are like those from Kerala—prepare early, and follow WHO’s mantra ‘test, treat, trace’ aggressively. Hong Kong, Singapore, and South Korea did 30-50 times more testing per 1 million population than India has done (see table in Part 2 of this article). These three countries along with Taiwan and Vietnam did not declare a national lockdown. Testing, case detection and isolation have a strong influence on ‘flattening the curve.’ South Korea was so confident of winning the coronavirus war that it even held national elections on 15 April when 44 million masked and gloved voters went to the polls to elect 300 representatives to the National Assembly.

India’s options to beat COVID-19

A vaccine for COVID-19 is 12-18 months away. A lockdown will not stop the spread of COVID-19. It can only slow it down. Lockdowns merely provide a little breathing space for preparing for the next move.

The lockdown in India has been extended from 15 April to 3 May, and in some states a little beyond that. What will India do after 3 May? India has only two options until a vaccine becomes available or coronavirus weakens.

The first option is to do repeated lockdowns (suppression strategy) when case numbers rise after a lifting a lockdown as populations do not acquire herd immunity in a suppression strategy.

Repeated lockdowns will further disrupt the economy and cause enormous stress to people, particularly to unorganized sector labour, the self-employed, and farmers. It will also keep the supply chain of goods and services broken, which could then trigger an economic slowdown. A health crisis could develop into an economic and humanitarian crisis of a huge magnitude, with the possibility of a rise in hunger, malnutrition, and disease, resulting in possible hunger deaths and suicides.

The second option is to adopt a mix of mitigation strategy measures (physical distancing, sanitizing, case isolation, quarantining suspected carriers, aggressive testing, widespread surveillance, closing educational institutions) for the entire country, and using localized suppression strategy (localized lockdown) wherever hot spots appear. It is a mix of what is being done in Kerala and what was done in Bhilwara.

This approach allows the general population to develop herd immunity. It also gives the battered economy a fighting chance to recover and provide income to unorganized labour, self-employed and farmers. But the number of cases will rise, though more slowly. And there will be attrition. A small fraction of the cases will turn critical and require intensive care. And if the health delivery system is not ramped up sufficiently, the numbers of the critically ill who may not get adequate medical attention will rise. Mumbai is already running out of ICU beds.

Since the Indian work force is relatively young, the risk of serious illness is low. But the vulnerable sections of population—over-65-year olds and those with co-morbidities must be protected from exposure to the coronavirus. Doing this will test India’s ingenuity.

Partnering with people

A lot that may happen in the coming critical months will depend on the disease control choices that government takes. If government adopts the second option, which can control COVID-19 as well as avert a humanitarian and economic crisis, it can be implemented effectively only with public support.

For that, government must be more forthcoming with information and become more transparent in its actions by holding public consultations on issues like virus transmission dynamics, lockdown triggers, and the pros and cons of different mitigation strategies. Government should also become more inclusive in its decision making by co-opting public into decision-making bodies.

The chances of winning the war against coronavirus increase if government emulates the Kerala model and makes people an equal partner instead of treating them as pawns to be locked down at government’s will and without offering an explanation.

Future challenges

Climate change is a more daunting challenge than coronavirus. The average global temperature rise is now 1.1oC above pre-industrial times. In 2015 governments of the world agreed that warming should be restricted to 1.5-2oC. The United Nations Environment Programme’s Emissions Gap Report 2019” (EGR2019) indicates that to remain under the 1.5oC redline, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions must reduce by 7.6% per annum for the next decade. But GHG emissions are currently growing at 1.5% per annum, and at the current warming rate we will cross the 2oC redline in about 2 decades and be 3-4oC above pre-industrial times by the turn of this century.

A 3-4°C warming will cause frequent extreme weather events; alter precipitation patterns; raise sea levels by ~1-2 m by 2100; create millions of climate refugees; shrink glaciers and reduce the Arctic sea’s ice extent; cause food and water shortages, increase hunger, deprivation, malnutrition, disease and poverty; degrade and destroy forests and biodiversity and decrease water, timber and other eco-system services they provide; cause a sixth mass species extinction; cause loss of employment; disrupt the world’s social and political order; and trigger social conflict.

Climate change impacts will be slow and almost invisible initially, but will grow exponentially, like the way COVID-19 cases grew. Without downgrading the priority given to the profits for businesses first outlook and upgrading the reducing risk for all people outlook, the impending climate change challenge cannot be met.

Food, water, health, and environmental security at the global level

For a risk minimization programme, people need three basic securities: food and water security, health security for natural and manmade risks, and environmental security.

In 2018, the United Nations (UN) spent approximately 15.1% of its budget on food security, 7.1% on health security and 1% on environmental security. The UN has three organizations for food (WFP, FAO, IFAD) security, three organizations for health (WHO, PAHO, UNAIDS) security and one organization for environmental security (UNEP). It has no dedicated organization for creating water security or doing risk mitigation.

If food and water, health, and environmental securities are to be boosted, the UN must setup a dedicated organizations for risk mitigation and another for water security and must readjust its US$ 53-55 trillion budget to boost spending on these three securities from the current allocation of 23% of its budget to 30%, and which may be increased by 2% each year until these three securities together get 50% of the UN’s budget in time.

Like climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic is a global problem and can be best solved through global cooperation. The South Asian countries have realized this and are discussing possible collective action in the war against the coronavirus.

Food, water, health, and environment security should become fundamental rights in India

Three sections of Chapter IV: Directive Principles of State Policy of the Indian Constitution deal with certain aspects of food, health, and environmental security (see Box 9). These directive principles should now be re-framed to make food and water security, health security from natural and manmade risks, and environmental security to become fundamental rights for Indian citizens. Guaranteeing these rights and delivering them is the state’s fundamental duty. Without these rights, the right to life can only mean a right to physical life and not social life.

The 2020-21 budgeted expenditure of the union government is Rs 30.4 lakh crores. Of this approximately 12.5% is for food and water resources (Agriculture, cooperation & farmers welfare; Food & public distribution; Fisheries; Animal husbandry & dairying; Water resources; Drinking water & sanitation) 2.4% is for health (Health & family welfare; Health research; AYUSH; Pharmaceuticals) and (0.1%) is for the environment. Fifteen per cent of the budget, i.e., Rs 4.56 lakh crores, has been allocated for ministries and departments concerned with food and water, health, and environment.

A ministry or department must be setup for risk mitigation and another for water security. To guarantee food and water security, health security and environmental security to Indian citizens, the union and state governments must allocate 30% of their budgets for these securities. The budget allocation for these securities may be increased by 2% each year until they become 50% of the union and state governments’ budgets in time.

The Economic Survey of India, 2020 states that India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was Rs 202.5 lakh crores in 2018 and estimates it to be Rs 217.5 lakh crores in 2019. The survey expected a 6-6.5% GDP growth in 2020-21, i.e., a growth by Rs 13.6 lakh crores. After the COVID-19 outbreak, the GDP growth rate for 2020-21 has been pared down to 1.9% to -2%. The loss to the economy will range Rs 9.5-18 lakh crores.

Allocation of 30% of the union budget, i.e., Rs 9.1 lakh crores for food and water security, health security and environment security is less than the lower end expected loss in GDP growth (Rs 9.5 lakh crores) and half the higher end loss in GDP growth (Rs 18 lakh crores). Even if the 30% allocation budget of the state and union territory budgets is added, this investment is well worth as it would more than compensate for loss of income and additional expenses that COVID-19 caused lakhs of families. The personal loss to families that lost lives cannot be measured in monetary terms.

More importantly, an investment in people’s welfare will move India towards becoming a nation that cares for its people, particularly its poor and vulnerable, and not be a nation that merely boasts of becoming a US$ 5 trillion economy by 2025. In the final analysis, is it not better to be a nation where we feel cared for rather than be a nation with a wee bit more money but with a dog-eat-dog attitude?

Reference:

[1] This needs validation by doing a more extensive analysis on a larger sample of countries and over a longer period.

[2] Computed from data available at the websites of Ministry of Health & Family Welfare and Wikipidia

Published earlier in Firstpost, 28 Apr 2020:

https://www.firstpost.com/health/coronavirus-outbreak-why-do-grey-rhino-events-reoccur-what-important-policy-shifts-are-required-part-4-8304721.html

The author is an environmental engineer with specialization in risk analysis

Back to Home Page

May 13, 2020

Sagar Dhara sagdhara@gmail.com

Your Comment if any

|